Ahead of yesterday’s Budget I was on Times Radio discussing what we could expect, I was then on BBC Radio 4’s World at One expert panel to discuss it before and after. You can listen back to my comments here. My pre-Budget comments were that the Chancellor will primarily focus on two areas: “the investment side…and the labour force supply”, while my post-Budget comments (from1:39:24-1:40:50) highlighted some technical policy changes.

You can also read my full analysis for Netwealth below.

This was first published on Netwealth – 16th March 2023

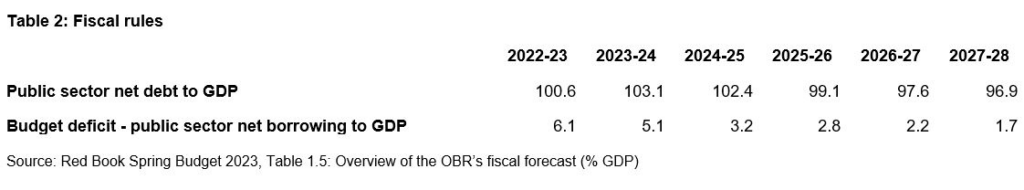

With debt set to be 100.6% of GDP at the end of this year, the relationship between growth and interest rates becomes key. If debt remains above 100% of GDP the economy is then in a precarious position – particularly if growth disappoints and if rates stay high because of inflation. In that scenario, the economy could slip into a debt trap, where the ratio of debt keeps rising. The UK is not in this situation yet, and should avoid it, but how this plays out with the relationship between nominal GDP and interest rates in coming years is key.

Perhaps this highlights why the Chancellor has chosen as one of his two fiscal rules the aim to have debt falling as a percent of GDP within five years. His other rule is to ensure the budget deficit does not exceed 3% of GDP. The UK has a track record of dropping its fiscal rules at the first sign of difficulty. It cannot afford to do so on the ratio of debt to GDP. This Budget meets both fiscal rules, with the budget deficit falling, but still leaves debt, tax and public spending at high levels.

This context also reinforces the need for the UK to raise its future trend rate of growth. The Chancellor focussed his November Autumn Statement on stability and focused this Budget on growth. He was right to do so, but more growth focused measures will likely be needed.

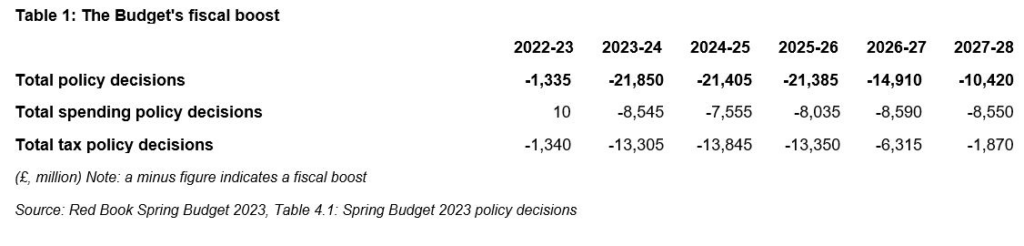

The fiscal numbers

Before assessing any Budget measures, it is essential to gauge the fiscal and economic backdrop. The good news is that the economic and fiscal numbers have proved better in recent months than was expected at the time of November’s Autumn Statement. But growth is still weak and improvement in the finances is reliant on the Chancellor’s choice of fiscal rules and various precarious assumptions about the future of the economy.

Nonetheless, the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) forecasts allowed the Chancellor increased fiscal headroom, two-thirds of which he has used on measures announced in the Budget aimed at addressing the cost-of-living crisis and boosting the supply-side of the economy. The rest he used to reduce borrowing. On the positive, the OBR’s growth forecasts have been revised higher and borrowing lower; on the negative, growth is still low and debt and taxes are high.

Despite these measures, the high rate of taxation remains an area to be addressed, as does tax simplification and reform. For instance, high marginal tax rates continue to exist at different levels of the income spectrum. Naturally, headline and marginal tax rates are important and should be seen as part of a wider growth agenda.

The margin of error on budget forecasts and on the fiscal numbers is high, even looking forward just one year ahead, never mind four or five. Compared with last November for instance, the budget deficit for this year is now expected to be £24.7 billion better – reflecting £14.8 billion in higher receipts and £9.9 billion in lower spending. In particular, the OBR notes that the fiscal numbers have “improved materially” in future fiscal years, by on average £24.5 billion per year.

Table 2 summarises the Chancellor’s fiscal rules, to have public debt falling as a proportion of GDP within five years, and to have the budget deficit no greater than 3% of GDP. These fiscal rules are met. Public debt is expected to fall to 96.9% of GDP over the next five years.

The options to reduce debt to GDP are: growth, austerity, taxes and borrowing, or a combination of these. Given these, and the current fiscal numbers, one can understand why a focus on growth is key. Austerity made no sense a decade ago, and is clearly not desirable now, although at some stage reform of public expenditure as well as taxation may be needed. Meanwhile, as we have stated before, tax cuts by themselves cannot deliver growth but taxes clearly form an important part of a wider agenda aimed at boosting growth.

Borrowing has been a policy choice, but in the wake of the rise in interest rates, the Budget focused on reducing the primary deficit (which is public sector net borrowing minus net interest rate payments) so that it is in surplus towards the end of the forecast period.

Fiscal policy – as we have seen during the pandemic and energy crisis – can play a vital role in helping stabilise an economy. But these numbers from the OBR cited above would suggest there is little fiscal leeway. Additionally, there appears to be limited immediate room for monetary policy manoeuvre. Hence to boost growth it is right that there is an increased focus on supply side measures, although as we saw today – on labour force participation and boosting business investment – these require significant fiscal aid, too.

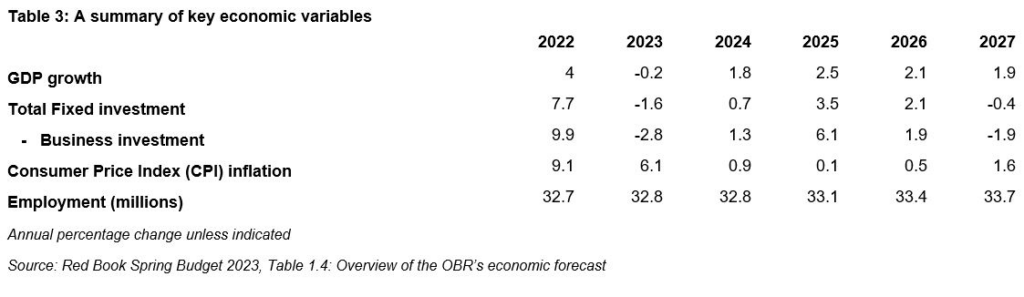

Economic numbers

Table 3 summarises some of the key economic variables to focus on as a result of this Budget: growth, inflation and in light of today’s measures, the level of employment and total and business investment. We have listed the latter, given the policy focus on these areas. Compared with their previous forecast in November the OBR now sees employment as 200k higher at the end of the forecast period. Interestingly, while business investment is forecast as being higher in the next year than expected in the autumn, it then remains erratic and low. Business investment is pro-cyclical but its expected weakness is notable given the policy focus.

Inflation looks likely to decelerate significantly this year – with the OBR expecting it to decelerate from 10.7% now to 2.9% by year-end – and undershoot its target next. The OBR’s forecast is then for inflation to undershoot its 2% target for some time, while growth returns to close to what may be perceived as trend. While inflation looks set to fall sharply over the next year, the projection for future years may prove optimistic.

Policy measures and implications

The Chancellor focused his measures on a number of areas: helping people through the cost-of-living crisis by extending, as widely expected, the energy price guarantee and through freezing fuel duty; a focus on the supply side of the economy with measures aimed at boosting business investment, encouraging R&D in science and technology, increasing the labour supply (that is the number of people in the workforce) with a welcome focus on childcare costs and a plethora of other measures to boost enterprise as well as to support both the green and levelling up agendas.

The latter included the announcement of a dozen new investment zones. There was a significant rise in defence spending but no net new money to address the current public sector pay problem. The Chancellor also announced that he will aim to unveil in the autumn his plans to, “build a larger, more diverse financial system” to allow more people to invest in high growth firms.

In fact, this was a Budget with 84 specific measures, many small and technical. Such an array of measures may suggest too much micro-managing, but some while not headline grabbing are welcome.

One such measure includes scrapping the Work Capability Assessment, which should incentivise benefit claimants to seek work without fear of losing their existing financial support.

Other measures, which will attract much attention, include increasing the tax-free annual pension contributions cap from £40k to £60k and abolishing the £1.072 million tax-free lifetime allowance on pension pots. The Chancellor will argue these measures will discourage workers (many of whom will be productive higher earners) from early retirement, while also stopping other workers such as doctors from reducing hours or retiring early owing to tax.

Critics of this policy will argue that if the latter was his concern, then specific changes to the public sector and NHS pension schemes would have been better targeted. Also, it’s possible these measures may encourage some to retire earlier. These changes may also focus attention on the issue of pension pots being free of inheritance tax.

Judging the success of a Budget is difficult, as the devil is in the detail – this is certainly the case for instance with the changes to child care. The immediate metric is how the financial markets react. They reacted well to the Budget itself, encouraged by the focus on stability, and the improved economic and fiscal numbers. The fiscal measures broadly passed the three tests of being necessary, affordable and non-inflationary.

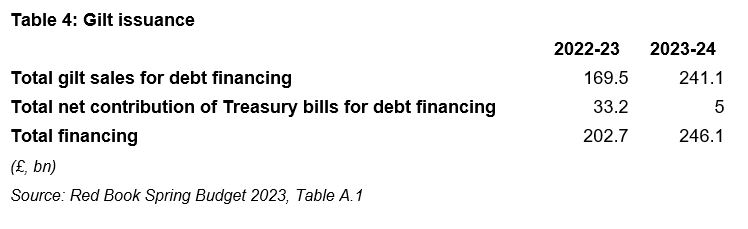

Almost all of the Chancellor’s announcements were covered in the media beforehand, meaning there was less likelihood of surprises spooking the markets. Table 4 shows the sizeable financing requirement in the forthcoming fiscal year, compared with this. This totals £246.1 billion, or which total gilt sales amount to £241.1 billion. Given the size of the borrowing requirement, it is important to keep the markets onside.

While the Chancellor’s change is positive and necessary, it is not permanent, lasting three years, and so is unlikely to lead to greater business investment overall – just more investment sooner. On the negative side, the hike in the corporation tax from 19% to 25% will still go ahead, which will impact the UK’s business competitiveness. What businesses would ideally like to see are permanent changes to the corporate tax system and capital allowances, not constant tinkering. When the time is right, the Government should move towards full-expensing permanently not just for plant and machinery – but also extend it to cover structures and buildings.

In conclusion

Finally, the Budget was unveiled against the backdrop of a deteriorating global financial environment. There are many interlinked factors explaining this, but a significant contributory factor is the ending of the cheap money policy that western economies have experienced since the 2008 crisis. This is being seen in terms of higher policy rates and quantitative tightening across western countries. While the UK banking sector appears to be in solid shape, the UK economy, financial markets and even monetary policy here will be impacted by the global fallout, and this has already cast a shadow over the upbeat message of the Budget.

The fall-out from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the US last week and current concerns about Credit Suisse, which is seen as too big to fail but very costly to save, are likely to exacerbate the downside risks for the world economy. Such an environment will likely require specific central banks to provide liquidity to help address the immediate crisis and to allow banks impacted to try and sort themselves out. This global context may also add to the pressure on central banks to pause their policy tightening.

Cheap money has led to asset price inflation, fed the current inflation environment, led markets to not price properly for risk and to a misallocation of capital. Banks and pension funds are often viewed as benefiting from higher rates, but it is the pace and scale of tightening and the speed with which cheap money ends that often causes the problem.

Thus, let’s return to the point raised in the first paragraph and the need to focus on growth. Following the measures announced in this Budget both the budget deficit and the ratio of debt to GDP are expected to fall steadily over the five-year forecast horizon. That is welcome. One historical lesson is worth bearing in mind, for as we saw in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the ratio of debt to GDP was far higher, it was able to fall steadily in an environment of solid growth in nominal GDP and financial repression, where interest rates were low. Success in the UK requires not only inflation and in turn interest rates to settle at a low level but requires the UK to enjoy stronger and sustainable growth.

In this climate, the Chancellor is right to stress the need to boost growth. In addition to the long-standing productivity puzzle, we have a participation problem and insufficient investment. The Budget was right to focus on supply-side measures to address these. However, there is still way to go to boost growth on a sustainable basis.